Learning from mushrooms could help to replace plastics in new high-performance ultra-light materials

The complex architectural design of mushrooms could be mimicked and used to create new materials to replace plastics.

A research group from VTT Technical Research Center of Finland has unlocked the secret behind the extraordinary mechanical properties and ultra-light weight of certain fungi. The research results were published in Science Advances .

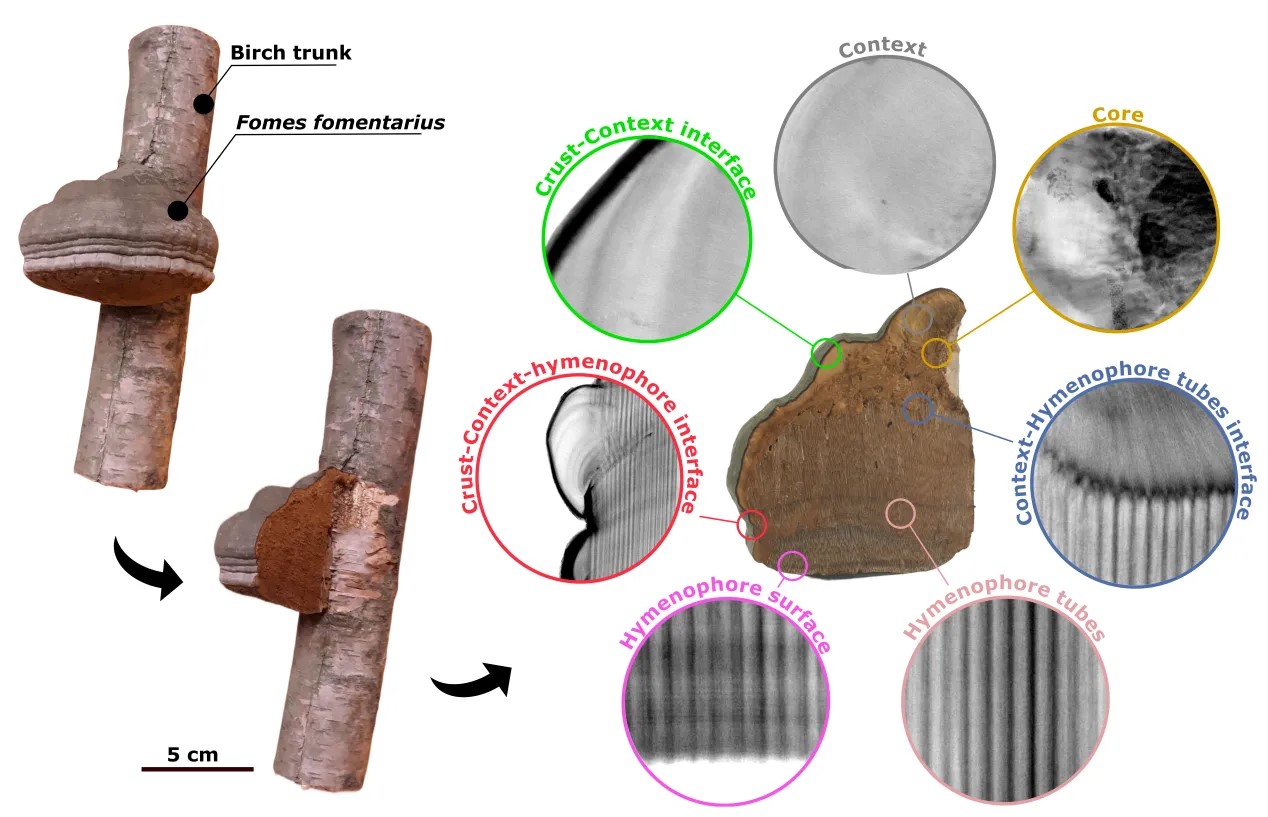

VTT’s research shows for the first time the complex structural, chemical, and mechanical features adapted throughout the course of evolution by Hoof mushroom (Fomes fomentarius). These features interplay synergistically to create a completely new class of high-performance materials.

Research findings can be used as a source of inspiration to grow from the bottom up the next generation of mechanically robust and lightweight sustainable materials for a variety of applications under laboratory conditions. These include impact-resistant implants, sports equipment, body armor, exoskeletons for aircraft, electronics, or surface coatings for windshields.

Unravelling the unique microstructure of Fomes fungus

Nature provides insights into design strategies evolved by living organisms to construct robust materials. The tinder fungus Fomes is a particularly interesting species for advanced materials applications. It is a common inhabitant of the birch tree, with an important function in releasing carbon and other nutrients from the dead trees. The Fomes fruiting bodies are ingeniously lightweight biological designs, simple in composition but efficient in performance. They fulfill a variety of mechanical and functional needs, for example, protection against insects or fallen branches, propagation, survival (unpreferred texture and taste for animals), and thriving of the multi-year fruiting body through changing seasons.

VTT’s new research reveals that the Fomes fruiting body is a functionally graded material with three distinct layers that undergo multiscale hierarchical self-assembly.

“The mycelium network is the primary component in all layers. However, in each layer, mycelium exhibits a very distinct microstructure with unique preferential orientation, aspect ratio, density, and branch length. An extracellular matrix acts as a reinforcing adhesive that differs in each layer in terms of quantity, polymeric content, and interconnectivity”, said Pezhman Mohammadi, Senior Scientist at VTT.

![EMR_AMS-Asset-Monitor-banner_300x600_MW[62]OCT EMR_AMS-Asset-Monitor-banner_300x600_MW[62]OCT](/var/ezwebin_site/storage/images/media/images/emr_ams-asset-monitor-banner_300x600_mw-62-oct/79406-1-eng-GB/EMR_AMS-Asset-Monitor-banner_300x600_MW-62-OCT.png)